Design thinking is a new, hot topic in the marketing industry that is an excellent tool for stirring creativity and innovation. In a nutshell, design thinking is a human-centered approach to problem solving and innovation. To learn more about the entire design thinking process, you can read our article d.Signing My Way Through San Francisco.

For a human-centered approach, one of the key components requires you to understand the people for whom you are trying to solve a problem. In order to do so, the process starts with “empathy interviews” to learn about your target audience, which includes uncovering their feelings and experiences. These interviews start with a loose topic. The interviewer looks for stories from their subject(s) that relate to the problem, being sure to ask questions regarding their emotions and motivations. To learn more about this process, read our article How to Conduct Empathy Interviews.

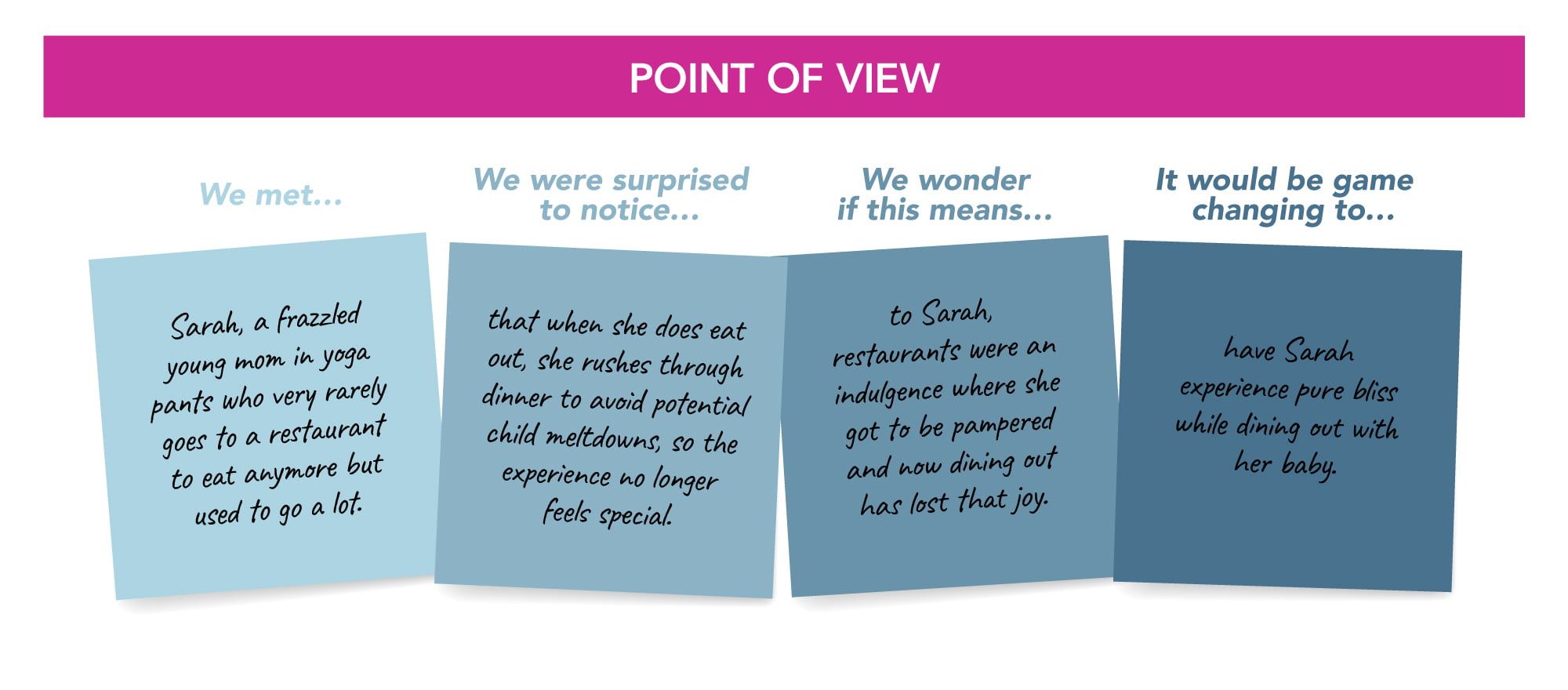

Once you’ve collected notes from your interviews, you’ll need to dissect the information and focus on one individual in order to develop your point of view (POV). Your POV will serve as a touchpoint throughout the rest of the process and help frame the problem you are trying to solve for.

In this article, we will analyze the key elements of a POV as outlined by Stanford’s d.school using an example from a recent design thinking project.

Our design thinking challenge

The restaurant industry is suffering from less foot traffic in-store, which is affecting profit margins. There has been a fundamental shift in the way people consume restaurant food, so we want to dig into this and see what we can uncover. For the purposes of this article, we will focus on this specific design challenge: Why are less people dining in at restaurants?

What is a POV?

A point of view is similar in some ways to a persona in that it focuses on an individual and their pain points for a particular situation. However, unlike a persona, the POV is based on information gathered from a real subject. That is not to say that a POV will be 100% true because part of the process involves making leaps or speculation to achieve an insight, but these leaps are grounded in reality.

The key criteria of the POV includes information of the person such as: a description, an unusual observance made in the interview, an insight inferred from that observation, and finally, what could turn that insight on its head to become a positive for the individual.

1. We met…

To begin outlining your POV, you want to paint a vivid picture of the person you interviewed. Jot down all relevant details that tie back to your problem. Start with a name. Even if you forgot to write down their name, give them one as it grounds you and makes the subject more realistic.

Write down physical characteristics such as gender, age, attire and even a personality trait or two, it will help paint a clearer picture. Sometimes it may be relevant to note where you interviewed the person or what they were doing when you approached them. Be specific but concise.

Let’s look at some examples from a recent empathy interview we conducted about eating out at restaurants. We’ll start with some common mistakes.

We met…a woman at the mall who was shopping with her mom.

This doesn’t paint a very good picture of the woman that we interviewed. There is no name and no detail. Is it relevant to our topic that she was shopping with her mom? Let’s try again.

We met… Sarah, a young mom, who doesn’t eat out very often.

This version is better. She now has a name and we know that she is a mom. The fact that she doesn’t eat out very often is tied back to our challenge; however, the description could be better.

We met…Sarah, a frazzled young mom in yoga pants who very rarely goes to a restaurant to eat anymore but used to go a lot.

While still a short statement, it paints a more vivid image in your mind of Sarah, and you can picture her. This gives us a good starting place to really dive in and get to know Sarah and her habits.

2. We were surprised to notice…

For this section we want to focus on something that you heard or observed from your interview that was surprising or unusual. Look at the contradictions in what you heard versus observed, or tensions in an answer that they gave. These are the things that are going to provide the best fodder for a leap to an insight later.

We were surprised to notice… now that she is a mom, she doesn’t go out to eat anymore.

Let’s be honest, this statement is not very surprising. Many new parents stop doing a lot of the activities they used to once enjoy, whether it is because of time or money. If this was something you could have known or guessed fairly easily prior to the interview, then it isn’t a surprise. Need a Litmus test? Ask a friend or co-worker if this statement would surprise them.

We were surprised to notice… when she does eat out, she feels rushed.

Here we talk a little about why she doesn’t go out to eat anymore but this is scratching the surface. Why does she feel rushed? What is the significance of feeling rushed? Think back to what she said during the interview.

We were surprised to notice…when she does eat out, she rushes through dinner to avoid potential child meltdowns, so the experience no longer feels special.

Now we have a better sense of what is happening in Sarah’s head based on what she said during the interview. The surprise should peak your interest in the subject. As we move to the next section, we leave behind the facts and instead turn to hunches and assumptions.

3. We wonder if this means…

Making a leap to an insight is often the most challenging part of crafting a POV. In this next section, we need to take the observation we made in the previous step and make an inference. While it should be grounded in your interview, it is a hunch and not something you heard or saw in your interview. This is the one time that you have free rein to make an assumption about someone. Push the envelope and look for that extreme possibility versus the safe or broad assumptions.

Based on our statement, we know that Sarah stopped going to restaurants after she became a mom. While it wasn’t time or money that changed her behavior, it was her reaction to the experience that changed. Instead of relaxing and enjoying someone waiting on you and cooking you a delicious meal, she instead felt like she had to get through the meal quickly in case her child had a meltdown at the restaurant.

We wonder if this means… she is worried people will be annoyed if her child misbehaves.

Sure, this is possible and probably plays a small part in why she feels rushed. Nobody wants to be that parent in a restaurant or on a plane with a child who is having a temper tantrum or won’t stop crying. Again, this is very surface level, we need to dig deeper.

We wonder if this means… she is worried people will judge her as a parent if her child has a meltdown.

This does give us some insight and a possible reason she doesn’t eat out, but is it extreme enough? Could you say this about a lot of parents? I think so. Sometimes you need to go back and revisit the surprise to come up with a better insight. Instead of focusing on the concern over the meltdowns, would it be more interesting to focus on the loss of fun for the event? That seems less expected.

We wonder if this means…to Sarah, restaurants were an indulgence where she got to be pampered and now dining out has lost that joy.

We get a feeling of emotion from Sarah in this statement that will allow us to come up with an idea that will be a “game changer” for Sarah.

4. It would be game changing to…

With a solid inference in place, it is time to figure out exactly what our “game changer” or design challenge will be. What can change things for Sarah?

It would be game changing to…have restaurants provide Sarah with a babysitter so she can enjoy her meal.

A common issue with setting up a game changer is jumping straight to a solution. That isn’t the point of this exercise. When you move into ideation, which is the next step in the design thinking process, you will look at solutions. But for now, it needs to be open enough that you can come up with a lot of possibilities. Ask yourself what is good about the idea? How could you turn that into something else? Is this something that already exists?

It would be game changing to…allow Sarah to revisit a time when she wasn’t a parent.

Time travel would be fun, but it isn’t truly realistic, and you need to make sure this doesn’t seem impossible. Plus, we want to make sure that our game changer relates back to the challenge.

It would be game changing to…have Sarah experience pure bliss while dining out with her baby.

This statement relates back her to dining experience and allows for a wide variety of options when it comes time to ideate. Let’s look at our final POV.

5. Evaluate your POV

With your POV written it is always best to spend a few minutes evaluating it. Sometimes you need to go back and re-word something, add more description, shorten it, or start over completely. Below are some simple criteria for best practices that you can check against your POV.

A spectacular POV:

- Focuses on an individual

- Uses sensical and strong language

- Contains a surprising observation and thought-provoking interpretation

- Generates possibilities

- Relates to the project challenge/question

If your POV checks off all these boxes, then you are ready to move onto the next stage—ideation. If not, go back and make changes until you feel confident that your POV is on target.

Conclusion

When working on a design thinking project, it is important to have a solid POV since design thinking is driven by human-centered innovation. In the above example, we created a clear description of our user, detailed a surprise that came out of the interview, developed a true insight based on what we heard in our interview, and finally, came up with a solid game changer that we can now use to develop our idea for a solution.

Now it’s your turn.