In the marketing industry, we’ve been told over and over again to listen to users. Articles and industry experts boast the benefits of putting your customer first. They know best. Mindful listening is the most crucial resource for ideation. You don’t know if your product/solution is successful until effectively listening to the end-user. The list could go on.

Don’t get me wrong, paying attention to your users is an invaluable tool. It is absolutely crucial to your design process. However, where I think most have gotten it wrong is that we rely too heavily on the listening aspect of user feedback. When conducting user interviews, it’s crucial that you don’t solely rely on exactly what users say. Looking past their direct feedback, and actually ignoring what they’re telling you, is the best way to spark innovative, ground-breaking ideas.

Incremental Ideas vs. Disruptive Solutions

When asking what they would do to improve a process, product, or solution, users tend to lean on incremental ideas. Ideas that would improve their immediate task or challenge at hand. Users very rarely can see the bigger picture or strategy, especially during a time-constrained conversation that often comes with user interviews. Your users aren’t at fault here—it’s only human nature to stay hyper-focused on what’s bothering you right then and there.

The Taxi Experience Example

Let’s use an example to frame this conversation. Think about the taxi experience as it existed several years ago. Before Uber entered the scene, if you asked people what they would do to improve their experience in a taxi, most would respond with the following comments:

- Charge me less for my ride

- Have the drivers clean their car more frequently

- Give me control over the air conditioning and music

- Allow me to feel safer and more comfortable during my drive

- Etc.

If those on the other side of this user feedback relied solely on what people were saying, taxis would have improved, but just by a little. Taxi companies, for example, may have required drivers to clean their cars more frequently or take customer service training so they knew how to provide a more enjoyable ride.

While these changes may have slightly improved the taxi experience at the time, they are incremental changes—changes that would only temporarily fix obvious pain points.

In contrast, no user at that time would give feedback suggesting the development of a new mobile application where drivers can create a more personal experience, charge you less, and be available anywhere at any time. Not to mention, recommend an idea that let’s drivers use their personal vehicles and allows users to be in control of the entire experience, from start to finish.

It takes a user experience expert to listen to incremental requests and provide disruptive solutions to the larger problem at hand. This is done by breaking the mold of being a “yes” man (or woman) and solving for what users actually need vs. what they say they want.

Understanding the “Why” versus the “What”

“A lot of times, people don’t know what they want until you show it to them.” – Steve Jobs

“If I asked my customers what they wanted, they’d have said a faster horse.” – Henry Ford

Understanding the “why” versus the “what” in user feedback can be a challenging task. Not everyone can do it as eloquently as Steve Jobs or Henry Ford. And no two strategies have the exact same approach, so feel free to pave your own path to innovation, depending on what works best for you.

Nonetheless, it’s important to always take a step back and look at the bigger picture and strategy at hand. When I approach a challenge, I find it helpful to write down specific quotes, feedback, and insights that stuck out to me during user interviews. Once things are written down, I usually find trends that can be grouped together into larger themes. That tells me that there are common problems among multiple users that are large enough to solve for. From there, I evaluate those themes and determine if I need to take a step back even further, or if I can move forward with ideation.

When those tactics fail, I try to give myself a few days to walk away from a project to let solutions churn in my head. Rome wasn’t built in a day, and neither are great solutions, so remember to give yourself the space you need to think. More times than not, if I am able to walk away from a challenge, I return with a fresh perspective and exciting new solutions.

Testing Your Ideas

If you’re in the middle of this process and need a Litmus test, run your solution by another user, co-worker, or friend. Grab someone that is easy to access so you don’t stop your creative process by “waiting for the perfect time” or “waiting for the perfect user.” In my opinion, any feedback is great feedback to work with.

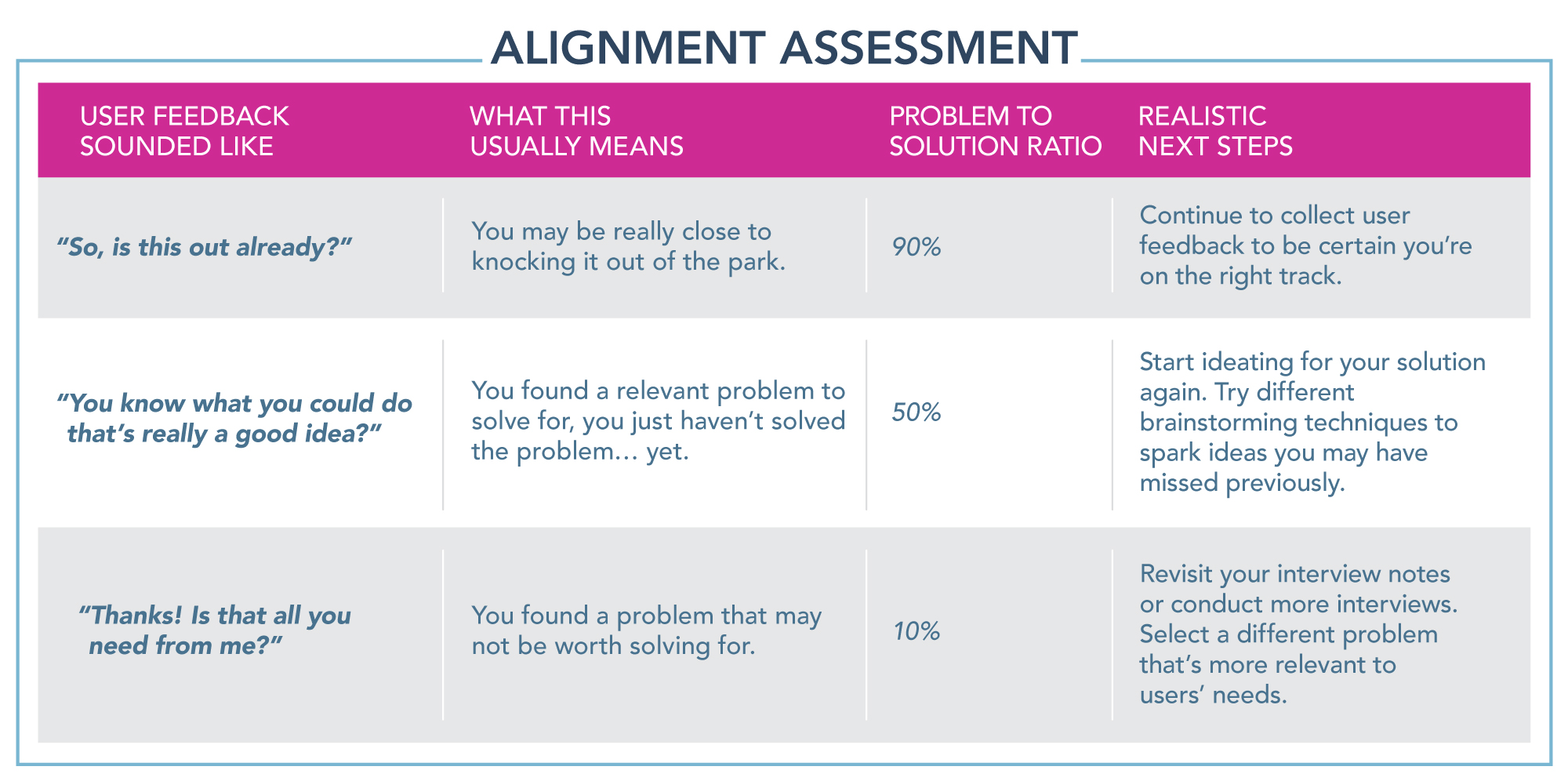

Once you present your solution and listen to feedback, you can quickly gut-check your ideas to ensure you’re on the right track. One of my favorite tools for testing my solutions is the following alignment assessment I picked up from my teachings at Stanford’s d.school for innovation and design thinking. The assessment identifies how closely aligned your solution is to your problem—helping you to stay on track and revisit points in your process if needed.

Knowing When to Break the Mold

Of course, not every solution is going to break the mold and become the next Uber, Apple, or Ford Motor Company. There’s a time and a place for disruptive ideas, so there’s no need to force yourself to reinvent the wheel every time a new problem comes across your desk.

Sometimes when a user gives feedback, it actually is the exact right answer—no matter how simple it may be. Trust me, this has happened in my experience more times that I can count. However, what I encourage you to do is to always take a step back and challenge yourself to think bigger before aimlessly jumping to a conclusion. That’s how great user experiences are created, and how you can push yourself to continuously stir up innovation in your thinking.

So, give it a try for yourself. You never know what great solutions you may discover along the way.