In the digital media world, the term user experience and its corresponding principles are applied to the development and design of websites. However, these principles can be applied to all channels including email marketing. User Experience, or UX, is defined as “the experience a person has when interacting with any touchpoint of a brand.”

When looking at email marketing specifically, what UX principles are applicable? How can these principles be used? And exactly how does UX meet email design? Throughout this series, we’ll cover all these aspects thoroughly.

UX Principles Can Be Applied Across All Marketing Channels

If you were to perform a simple Google search for “the principles of user experience,” you’d receive millions—3,890,000 to be exact—of links, articles, and resources dishing out various takes on this popular search term. At our agency, our devoted UX team has dissected, researched, and critiqued many of these approaches and techniques.

Between the millions of resources and articles and our company’s own expertise and knowledge, we’ve identified a specific set of six persuasion principles that we apply as part of all UX projects, be they website or other. These principles are Cialdini’s 6 Principles of Persuasion. Developed by Dr. Robert Cialdini, these principles, along with many others, are deeply integrated in all that we do at Zion & Zion including advertising, writing, UX design, web design, and email marketing.

Cialdini’s 6 Principles of Persuasion

Dr. Robert Cialdini is not the only researcher in social psychology and persuasion, but he is one of the most prominent ones. And with dozens of published academic articles, 35 years of rigorous, evidence-based research, and a wide range of credible research collaborations—one of the most trustworthy resources too.

Throughout Dr. Cialdini’s extensive work in the social psychology field, he was able to distill his work, and the work of many other researchers, down to 6 core persuasion principles, including:

- Reciprocation

- Commitment and Consistency

- Social Proof

- Liking

- Authority

- Scarcity

Although these principles are intuitive, understanding why and how they work can help you understand how to make each more successful. And even better, allow you to build a strategic framework around these principles to both leverage your brand and build long-term relationships with your audience—whether it be B2B or B2C.

Understanding Cialdini’s First Principle of Persuasion: Reciprocation

This article will focus entirely on the first of the seven persuasion principles, reciprocation. Cialdini describes reciprocation as the following:

We feel obligated to repay someone when they have given us something.

Follow along as we cover what reciprocation is, the proof that supports this principle, examples of reciprocation, and finally how you can apply this concept to your email designs.

What is the Reciprocation Principle?

The reciprocation principle seems intuitively obvious, but it’s incredibly powerful. It’s based on the premise that just the mere fact of someone doing something for you—even if it’s unwanted or not valuable—triggers an emotional response.

As an example, think about when somebody gets you a gift around the holidays and you forget to purchase something in return. In situations like these, we’re faced with an overwhelming feeling of guilt. Just being given something makes us feel in debt to the giver. We immediately plan for future acts of reciprocation to make up for this feeling of guilt.

The Proof

There are many studies and evidence that back up the principle of reciprocation. But for the purposes of this article, we’re focusing on just a few including the Regan study and the Krishna Society.

The Regan Study

The Regan study was an experiment conducted by Professor Denis Regan at Cornell University. The task in the study was to rate art. The twist to this study was that one participant was a true, unbiased participant, and the other was a confederate of Professor Regan. We’ll call the confederate, who was Regan’s assistant, Joe.

Throughout the various experiments, Joe was instructed to perform one of two tasks. In the experimental condition, Joe went on a 2-minute break and came back with a Coke for himself and for the other true participant. In the control condition, Joe came back empty handed. Besides this action, Joe’s behavior was the same as the other participant.

After all the paintings had been rated and the experimenter left the room, Joe asked the other participant for a favor. Joe, the confederate, told the naïve participant that he was selling raffle tickets for a new car. Joe then asked the other participants if they were interested in buying tickets. He mentioned that even a small amount would help.

The results showed that the participants in the experimental condition bought twice as many raffle tickets than the participants in the control condition who had not received a Coke. Later, Regan evaluated how liking, and compliance played a part in this study. He found that the relationship between liking and compliance was wiped out by whether the participant received a Coke. Meaning, that it didn’t matter whether the participant liked or disliked Joe; those that were given a Coke gave the same amount—proving that the principle of reciprocation is powerful enough to overcome the factor of dislike for the requester.

The Krishna Society

The Krishna Society used the principle of reciprocation to help fund their organization by targeting various travelers at airports.

Their tactic was simple. Members of their organization would approach an individual at the airport. They would then give that individual a flower. The Krishna member would say that the flower is of no cost, it’s a gift—completely free.

Many times, the targeted individual didn’t want to take the flower for several reasons. Either their hands were too full of their other baggage, or they simply didn’t have time to stop and converse with the giver. However, there they were, an unsuspecting passerby who suddenly found a flower pressed into their hands. They are under no circumstances allowed to give the gift back to the Krishna member, as they are refusing to accept it.

Once the targeted individual realizes they cannot give the flower back, they immediately feel in debt to the giver. At this point, the Krishna member has brought the force of reciprocation to the situation. Only after, does the Krishna member ask the individual to contribute to their society. Because of the undeniable force of reciprocation, the individual complies, giving money to the requester.

What’s important to point out here was that, in most cases, the flower was completely unwanted by the individual. This serves as proof that even uninvited gifts and unwanted situations generate feelings of obligation and reciprocation.

The Support

Now that we’ve discussed what the first principle of persuasion is and how it’s proven, let’s move onto the support. Here, we’ll cover three examples of reciprocation in email design—identifying where the principle is being implemented and if it’s working.

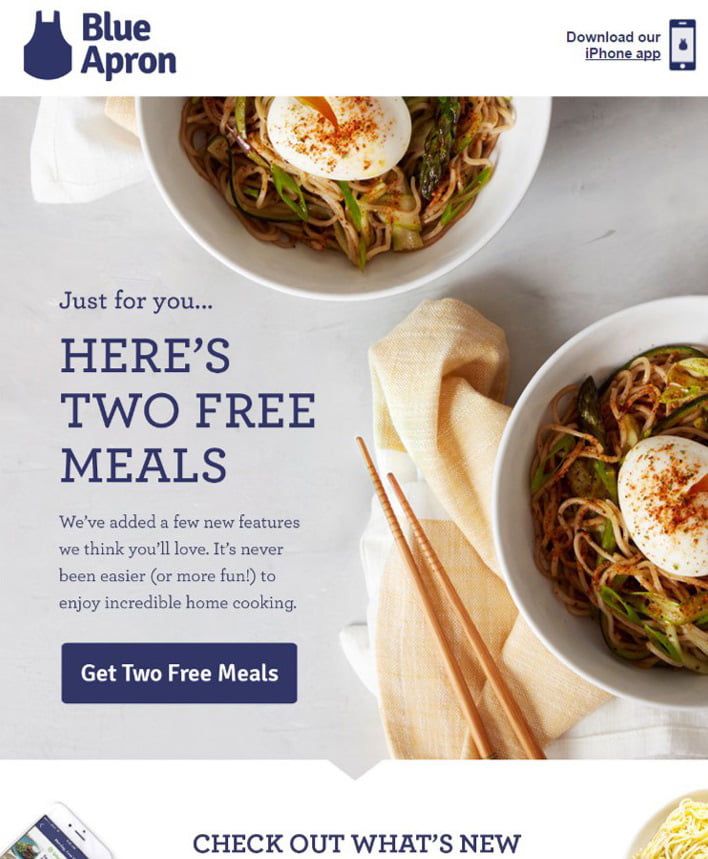

Blue Apron

The first email design that we’ll point out is by Blue Apron. Blue Apron utilizes reciprocation by listing out, “Here’s two free meals.” They’re giving away a product, hopeful that their audience will experience some form of obligation, so that the next time they see Blue Apron, they’re more enticed to make a purchase.

While this email design has in fact insinuated feelings of obligation and reciprocation, it could have been conducted better. For example, look carefully at their emphasized text. The company simply states, “Here’s two free meals.” This would be the same thing as someone coming up to you and saying, “Here’s your birthday gift.” While this does produce feelings of obligation, it’s not the best. Rather, Blue Apron could have mentioned something equivalent to, “Hi there! I wanted to celebrate your birthday with you, and that is why I bought you this gift. I hope you love it!”

Blue Apron could work on their wording to amplify the sense that they’ve put effort into supplying the offer to their customers by personalizing it a bit further. In the end, the effort and sentiment is the customer reciprocating what’s, not just the physical product. If Blue Apron were to go the emotional direction, it would trigger the customer to respond with similar emotions rather than just a transaction. This could change the customer’s mindset from “You gave me a product; I may give you my business” to “You value me as a customer, you gave me a free product; I will give you my business and may also give you my long-term loyalty.”

So, when designing emails, make sure you’re using language that makes your offer come across as a gift or favor—that you’ve put in effort in supplying it. The more you do this, the more reciprocation you’ll trigger.

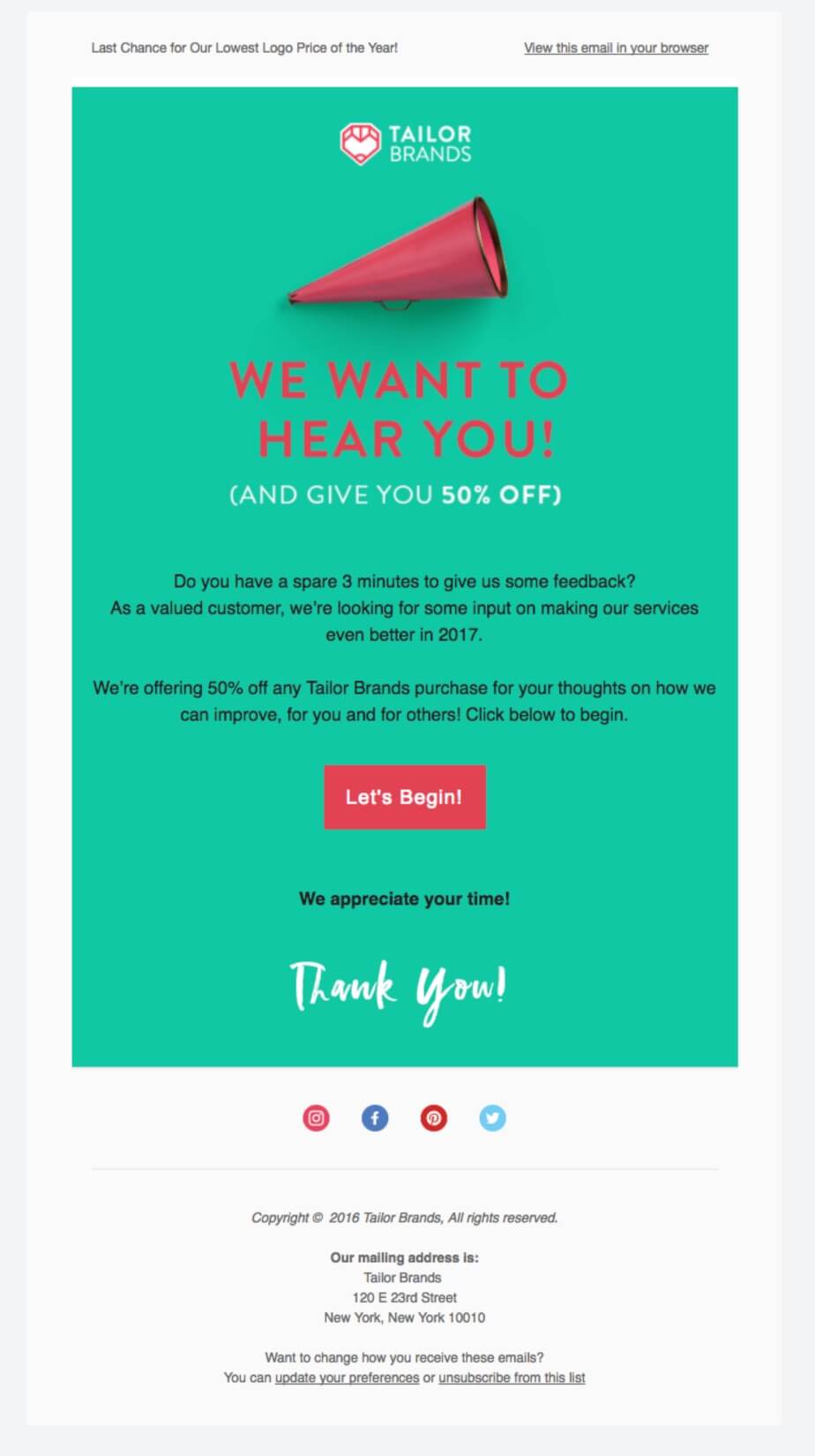

Tailor Brands

In this next B2B case, we can see a clear example of the reciprocity principle. Tailor Brands, a company that helps entrepreneurs build their business, is inviting its valued customers to share their feedback by leaving reviews. It is through this act of engagement that the principle comes into play, fostering a sense of mutual benefit and goodwill for both the brand and user.

By offering a substantial 50% discount on their customers’ subsequent purchases, Tailor Brands not only demonstrates their commitment to customer satisfaction but also acknowledges the intrinsic value of customer input. This reciprocal exchange is a testament to their dedication to building lasting relationships and ensuring the happiness of those they serve.

Furthermore, it is worth noting that the messaging employed in this communication is both straightforward and easily comprehensible. This clarity ensures that the reciprocity principle is effectively conveyed, making it a stellar example of how businesses can implement this concept to foster positive connections with their customers.

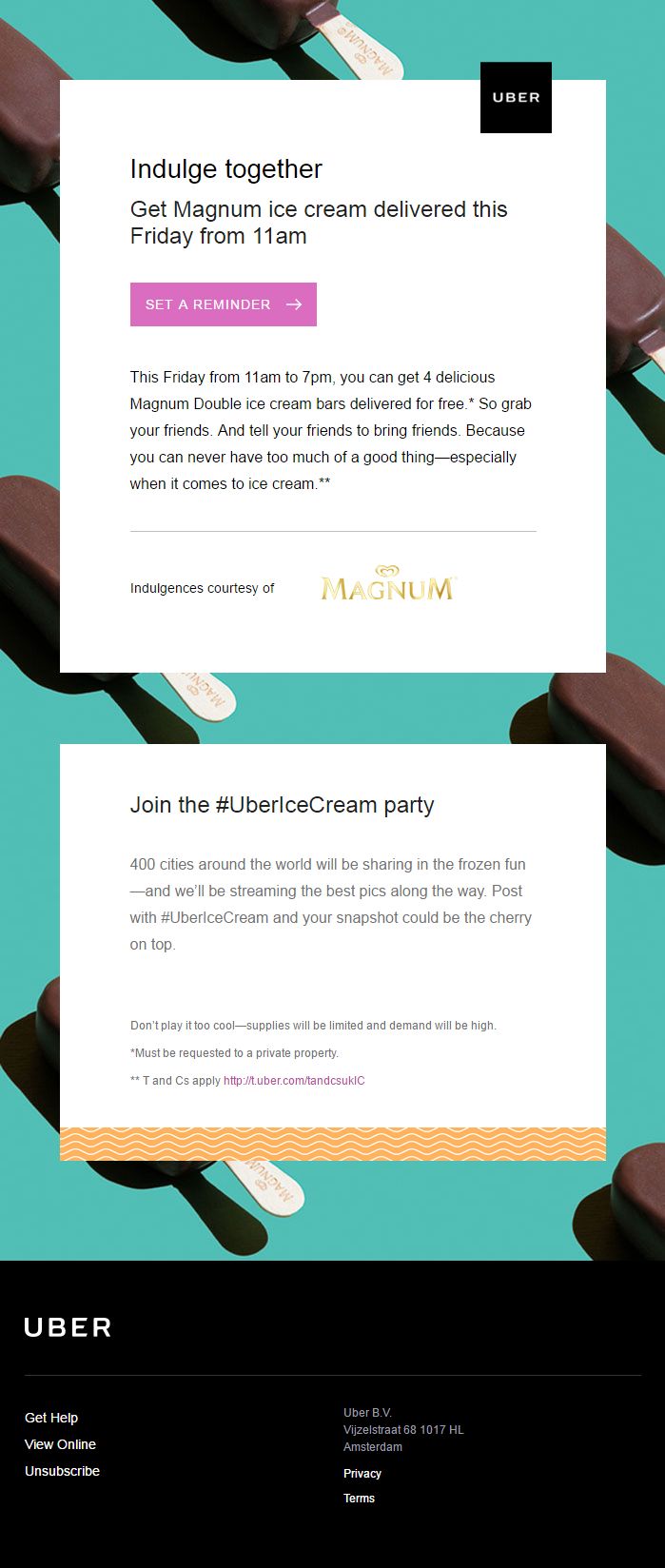

Uber

Our last example for the principle of reciprocation comes from Uber. In this email, the company is giving away ice cream. This is an interesting item to give away because instead of being a product or service the company provides; the free item represents what the company wants their users to associate to their brand. It’s something that makes the user feel a wide array of emotions.

First, free ice cream can make the customer feel taken care of. For example, when many think of ice cream, they think of their childhood, parents, or a sweet treat on a hot summer day. Overall, these thoughts invoke the emotion of being cared for.

And second, the free ice cream instills the emotions of being fun and exciting—because who doesn’t love free ice cream? Uber is bringing sweet treats to their audience to show that they’re fun and they want their customers to have fun too.

These factors allow the email to come across as an emotional investment on the brand’s part as opposed to just the coordination of giving away a free product. Think about what you’re offering in your emails. What you’re giving away should help build your brand association as well as trigger reciprocation.

The Application

When applying reciprocation to email design, always try to utilize emotions over the product itself. Showing your brand’s emotions invokes more obligation within your user as opposed to just simply giving a product and hoping for a transactional interaction. This is why the investment of just a few more minutes spent on the design, wording, or offer of an email is well worth it. A few simple tweaks can amplify the value of what you’re offering from a purely product or service level to an emotional level. Up next, you’ll learn how to leverage the second principle of persuasion, commitment and consistency.